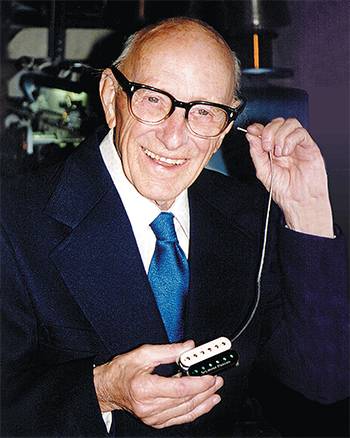

Seth Lover isn’t just a name that you’d find on a humbucker product page of a website. He was a talented electric engineer who not only designed the first PAF (Patent Applied For) humbucking pickup, but also designed among other things, the Maestro Fuzz pedal and a bunch of now-legendary amplifiers.

Early Life

Seth was born on January 1st, 1910 in Kalamazoo, Michigan. Even at an early age, he showed a great aptitude for electronics. The vast amount of development in the musical and studio recording fields actually came from the radio and telephony industries. Specialist magazines and even newspapers would print schematics for radio projects for electronics enthusiasts to build at home. Such was the quality of the information within these publications that it gave its readers a very good grounding in the practical and theoretical aspects of electronics. Many went on to study these topics further. As the early advent of the electrification of musical instruments began, many of these young engineers saw a new avenue for their skills.

This was a path taken by a young Seth Lover. With the encouragement of both his grandparents and teachers, his knowledge quickly grew. He even built his own valve radio from scratch as a young teenager. After graduating from school and working through a succession of jobs, Seth eventually enrolled in the US Army.

Armed Forces

Seth’s first stint with the US armed forces came in the early 1930s where he was part of the 16th Field Artillery. There he gained much more knowledge and experience as a radio engineer. As he left the Army, he signed up for a radio-electronics course to further his education in a subject he was now clearly very adept at.

At the start of World War II, Seth rejoined the army. Spending a lot of time teaching basic electronics and radio operations. During the war, he was transferred to the US Navy where he continued working as an electronics instructor.

Gibson

After Seth’s first enrolment in the US Army, he had gained enough experience to open his own radio repair shop in Kalamazoo. One of his customers, an orchestra leader names Eddie Smith, asked Seth to build him some small amplifiers for the quieter instruments within the orchestra. At this time, this mainly meant the guitar. Whose sound was often drowned out completely by the loader piano or drums. These first amplified guitars were used to great effect for a number of years, so it was no surprise, given Seth’s location in Kalamazoo, that Gibson would make contact.

Seth started working for Gibson in 1941 as an amplifier engineer. At the time, Gibson were not making their own amplifiers. Opting to buy amplifiers from local Chicago companies. Seth’s job was to test the amplifiers and troubleshoot and repair any issues before they could be sent out to Gibson’s network of dealers. This first job at Gibson lasted until Seth rejoined the US Army.

After World War II, Seth returned to Gibson for a few years. Working on products such as the optical tremolo and the GA-50 amplifier.

Seth was briefly tempted back to the Navy. Splitting his time between working for the Navy and Gibson for many years.

With Gibson’s new focus on the possibilities of the electric guitar, they invested a lot of money into various projects. The most famous of these would be their work with Les Paul. After initially discounting Paul’s design they soon saw the popularity of their new rival company, Fender, and redoubled their efforts. Designing a new flagship guitar design, the Les Paul model was born.

While this massively helped Gibson’s sales figures, it is well documented that Les Paul himself wasn’t 100% happy with the design. Some early photos and even some episodes of the popular Les and Mary show were released showing Les using his signature model guitar but with a replaced DeArmond Dynasonic pickup in the neck position the Les had fitted himself. This obviously highly upset Gibson. The idea that Gibson’s superstar artist needed to modify his own signature model with some other company’s pickup was very embarrassing for this prestigious guitar brand.

Gibson’s president at the time, Ted McCarty asked Seth to design a new type of pickup that would beat DeArmond at their own game and supersede the Dynasonic pickup. Hopefully, this would keep Les Paul happy and remove the need for him to tinker with his signature guitars anymore.

Seth’s design, with its rectangular polepieces and Alnico V magnets, became known as the ‘staple single coil’, and was Gibson’s answer to the Dynasonic. With individual screws for polepiece height adjustment.

This new pickup was fitted to Gibson’s 1953 Les Paul Custom, along with a few of their top-end ES Jazz models. The success of this pickup was enough to convince Gibson to match Seth’s Navy salary and allow him to rejoin Gibson full-time.

Seth Lover and the Birth of the 'bucker'

By the mid 50’s the electric instrument evolution was out of its infancy. Guitarists were now wanting to improve their sound, both live and recorded. There was one thing that plagued all electric guitar manufacturers. The same complaint was coming to them from all sides. Hum.

Specifically, 50 cycle hum, picked up by the single coil pickups. Given that these pickups are basically inductor coils, it wasn’t surprising that this issue would raise its head.

Seth’s solution to this problem actually came from his previous work with amplifiers. He took the idea of using a humbucking choke, that he’s used in the Gibson G-90 amplifier. This choke used a well-known electronic principle to eliminate the electrical ‘pick up’ from a power transformer. A transformer has two coils of wire wrapped around a magnetic core. Seth worked out that if a pickup was made with two coils, this would cancel out the hum in exactly the same way.

The principle of having two coils electrically out of phase and with a reversed magnetic polarity would cancel out the hum before it got to the amplifier. Exactly the same way that his original amplifier choke had worked.

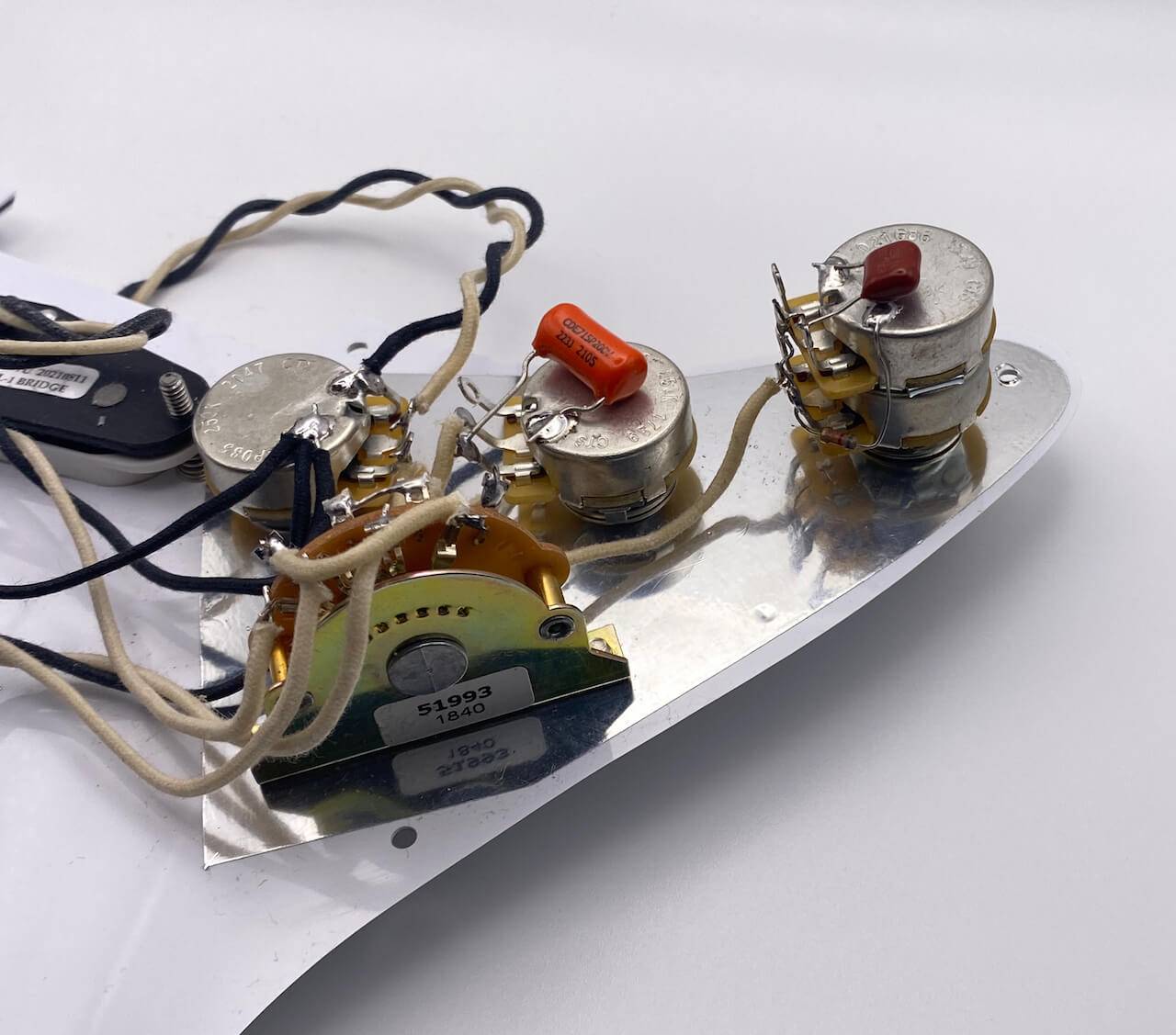

To test his theory, Seth constructed some prototype pickups and fitted them to two 1954 Gibson guitars. This original PAF prototype borrowed heavily from the P90 pickup design Gibson was already fitting to a lot of their models. They both shared a lot of the same internal components. As you can see if the photo, this original prototype even uses modified P90 bobbins.

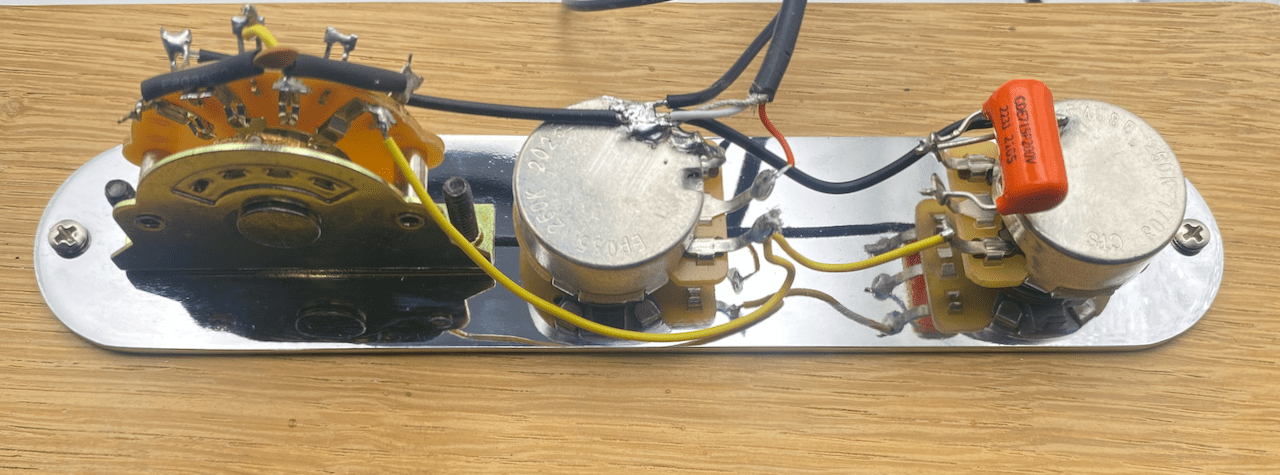

The original design and the prototype carried two sets of slug coils. Seth was persuaded to fit adjustable screw coils to one of the bobbins for the production models. Seth is documented as saying that this was technically unnecessary. The screw coils were simply added to give Gibson’s sales reps something to talk about. Even the position of the screw coils, with the neck screws facing towards the fretboard and the bridge screws facing towards the bridge, was done purely for cosmetic reasons.

This production model became known as the PAF pickup. Seth had applied for the patent in 1955, but it was only finally granted in 1959 (U.S. Patent 2,896,491)

During this five-year interim period, Gibson placed a “Patent Applied For” sticker on the underside of the humbuckers. These pickups are now some of the rarest, most valuable, and most copied humbuckers in the world.

While Seth was at Gibson he designed a few other notable pickups, including a shrunken version of the PAF, known as the mini-humbucker and an offset three-screw design (more on this concept later) for the Epiphone brand known as the P-19.

Fender

While still working for Gibson, Seth received a call from an ex-colleague, Dick Evans in 1967, who had left Gibson for a role as chief engineer want Gibson’s biggest rival, Fender. Evans asked if he would be interested in an engineering role, so Seth flew out to California for the interview. He was offered the job at $3000 more than Gibson were currently paying him, so he took the job.

He and his wife, Lavone, relocated to California where Seth started work for Fender as a project engineer. He stayed at Fender until his retirement in 1975.

Although Seth was at Fender for a number of years, he always felt that management, including founder Leo Fender, thought of him as a “Gibson Man” and an interloper in their business. By this time Fender had been bought out by CBS, who wanted Seth to design a new humbucker to rival the ‘Gibson sound”.

Leo would clearly not have approved of this idea, nor the engineer assigned to the project. On this, both Leo and Seth were in rare agreement. Seth’s view on the Fender guitars was that they were all about the treble response. Not the darker sound that he had sculpted for Gibson. These were two totally different machines and one should not sound like the other. Both were obviously keen to keep the “fender sound” intact.

Seth started his design process with the clear idea to keep the brighter “Fender sound” with a humbucking pickup. At the time, the high costs of certain alloys, such as Alnico, for the magnets forced Seth to investigate other alternatives. After a short R&D process, Seth settled on an alloy of copper, nickel and iron, known as Cunife.

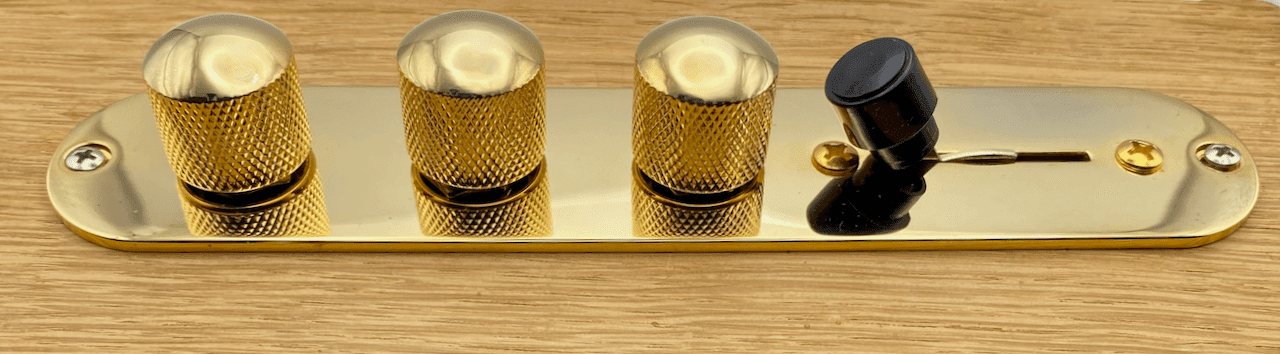

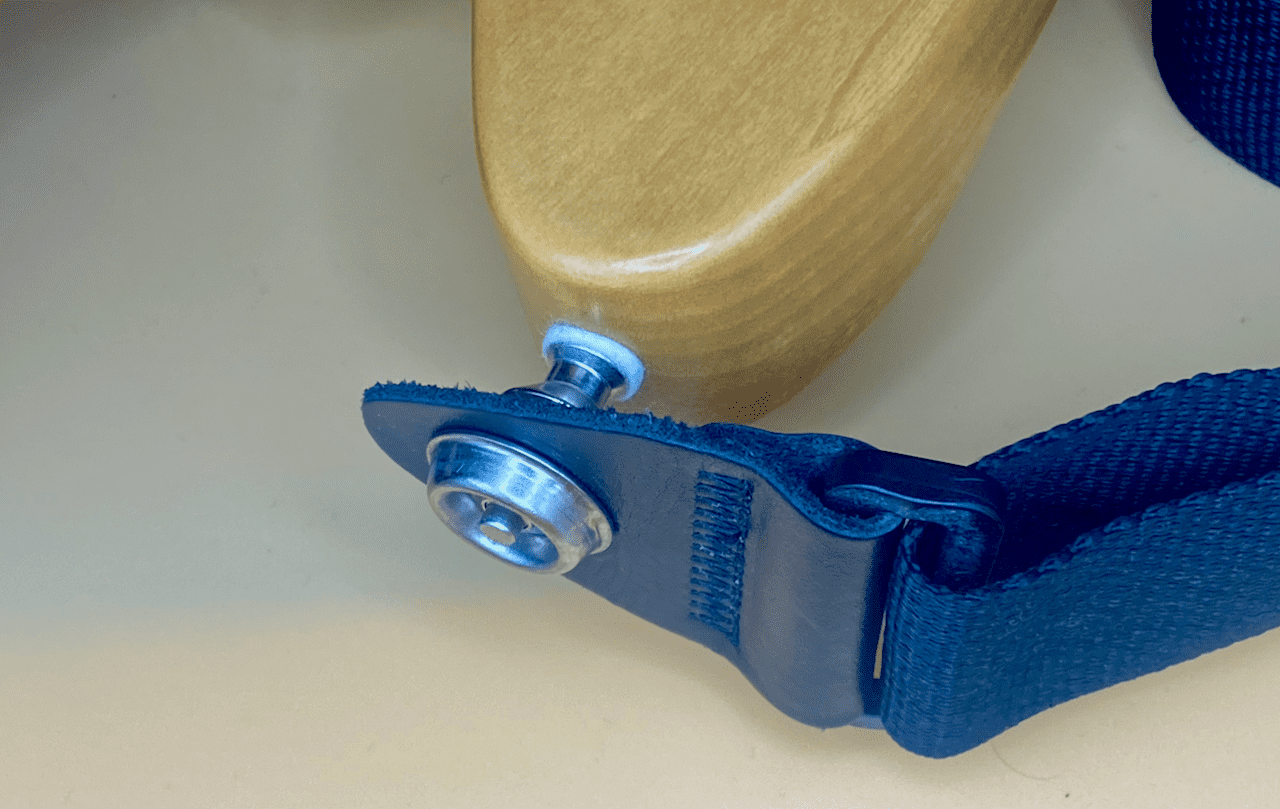

For the new pickup design, Seth was following the traditional Fender single coil pickup slug pole design by using permanent magnets for each polepiece. A benefit of using Cunife was that it could be machined and threaded, making it possible to manufacture screws from it. Seth took inspiration from his previous offset arrangement used in the Epiphone P-19 pickup, but this time designing them on an even bigger footprint than the PAF.

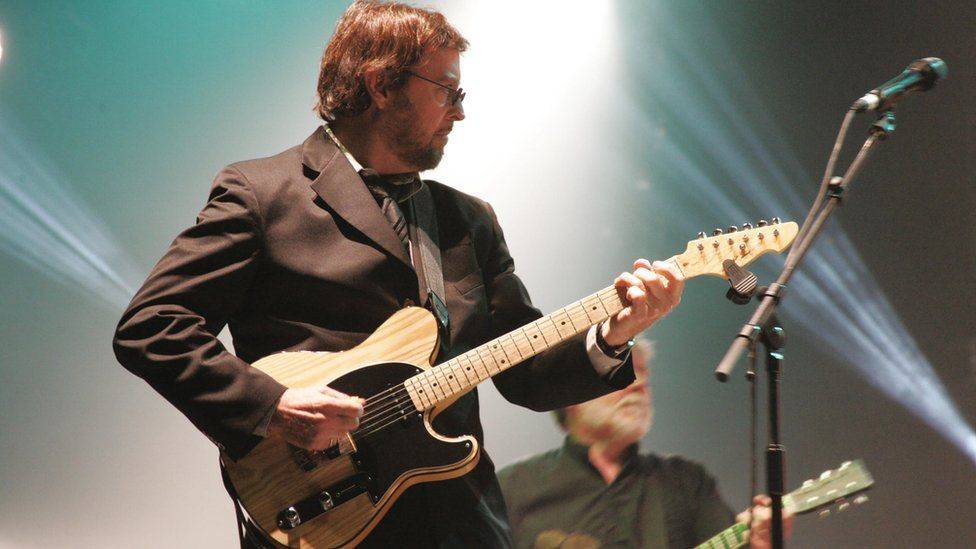

Fender’s new pickup design, known as the Wide Range Humbucker, was used in models such as the Telecaster Deluxe, Telecaster thin line, Telecaster Custom and the Starcaster.

This marked the high point of Seth’s innovation with Fender. None of his subsequent designs ever really went anywhere. He revisited some effects pedal ideas, as well as a ‘special effects’ guitar with on-board fuzz tone and auto-wah, but most designs never made it into production.

When Fender began work on their solid-state amplifier line, Seth was brought in to troubleshoot various issues with manufacture. Although creating a substantial report, detailing manufacturing issues, substandard parts, bad soldering and other reliability issues, the report was largely ignored.

Seth Lover retired from Fender in 1975…….

Seymour Duncan

Seth hadn’t been retired for a full year before one of the next generation of pickup manufacturers would come calling. By the mid 70’s a few aftermarket pickup manufacturers had started to gain a lot of credibility within the music industry. One of the biggest names was Seymour Duncan.

Seymour had realised that the 70’s fascination with ‘hot-humbuckers’ wouldn’t last forever. He had worked with a number of artists over the years and had the chance to get his hands on some of these early ‘vintage’ pickups.

There was something special about them, so Seymour decided to find out how to make these original pickups properly. This was the mid 70’s, there was no internet to quickly Google search a list of parts and a number of instructional videos on pickup assembly. Luckily, Seymour knew that one of the pioneers of this technology lived about 3 hours’ drive away.

Seth Lover and Seymour Duncan worked together for almost 20 years. In 1994, the pair collaborated on the Seth Lover Humbucker. The most accurate reproduction of the original PAF humbucker.

Each one (reputedly) wound on Seth’s own Leesona coil-winding machine, which Seymour Duncan now owns. The Seth Lover Humbucker is also the basis for the Antiquity PAF.

Seymour Duncan refers to Seth Lover as his “humbucker mentor”.

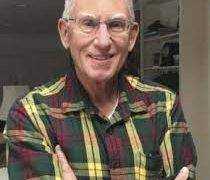

Even though it took until his 80’s after numerous Seymour Duncan adverts, NAMM show appearances and interviews on both television and in magazines, Seth Lover finally gained the respect and admiration (and a little bit of celebrity status) he deserved.

Seth Lover died on January 31st 1997 after a short illness.