George Fullerton –

Isn’t exactly a household name when it comes to the Music industry, apart from those more techie historians who look into where the designs come from. For people in the music industry, his designs are everywhere. They still form the bedrock of any new design for either hardware or complete instruments. His effect on the music industry as a whole can not be overlooked. It would be pretty hard to find anyone with hands-on experience with so much of the nuts and bolts of a whole industry, creating a legacy that will last for a very long time.

Early Life

George Fullerton was originally born in Arkansas. His family soon moved to the appropriately named Fullerton in Golden State. Not much is known about George’s early days, safe to say that he was extremely practical and musical. He was a skilled woodworker and metalworker as well as working in a local radio repair shop while also attending the local Junior Collage to study electronics. Still finding time to play in bands in the evenings.

Fender

George first met Leo Fender in the late ‘40s during a series of open-air concerts where local musicians would gather and play fairly regularly. Leo would provide the audio equipment and PA systems for the concerts. Before long, George was helping him set up. As George told Vintage Guitar magazine in 1991, he used to also visit Leo’s record shop fairly regularly too. One day Leo showed him a small electric guitar that he and Doc Kaufmann had built. Leo allowed George to try it out with this band. This seems to have been the spark that started everything. Leo could see the technical knowledge that George had and his interest in a wide variety of subjects and more importantly, how they all worked together. By February 1948, George Fullerton was working for the Fender Music Company.

Initially, with his background in electronics, George started repairing amplifiers. Later that same year, George started working directly with Leo to design the first Prototype solid ‘Spanish Electric’ guitar.

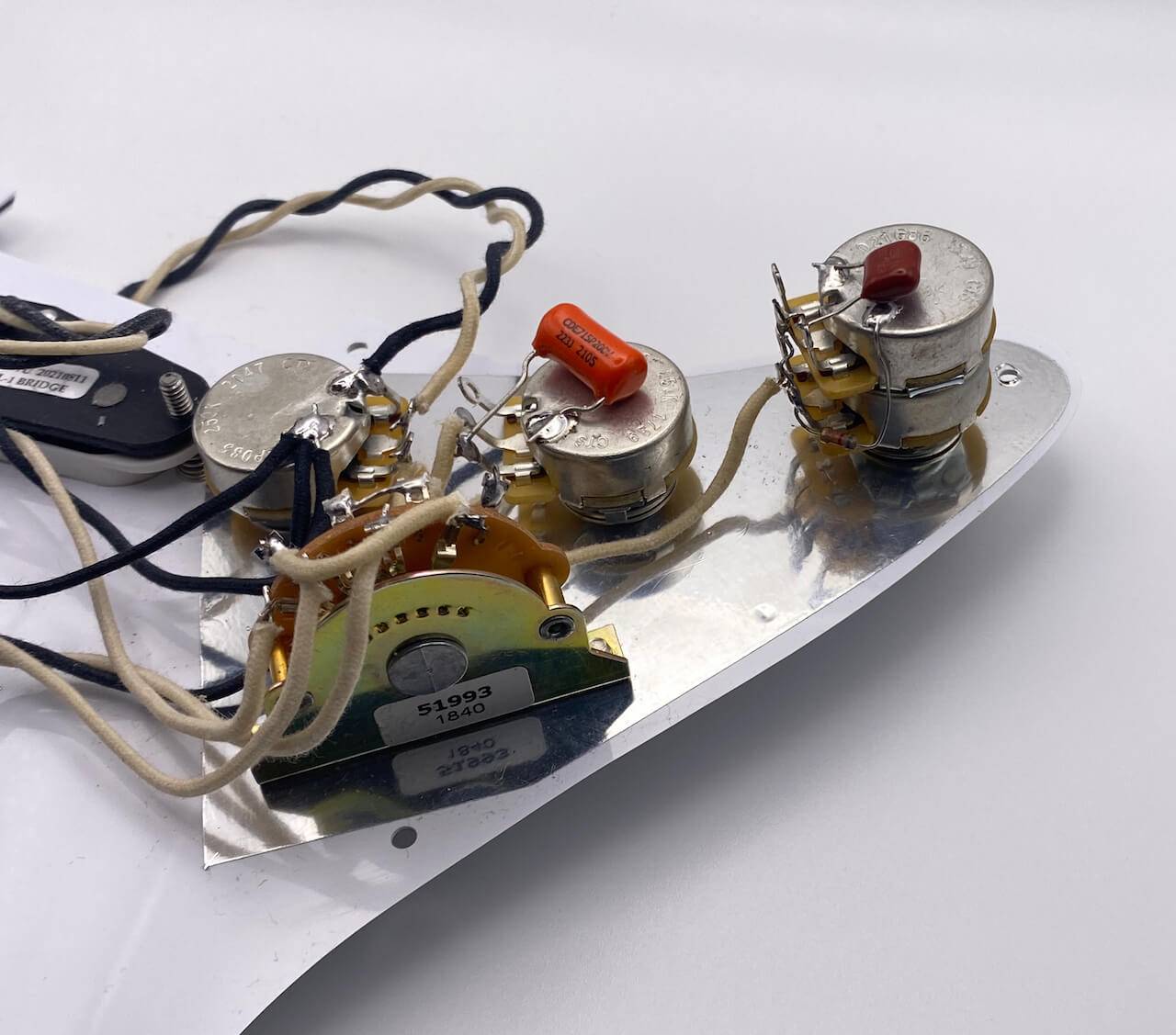

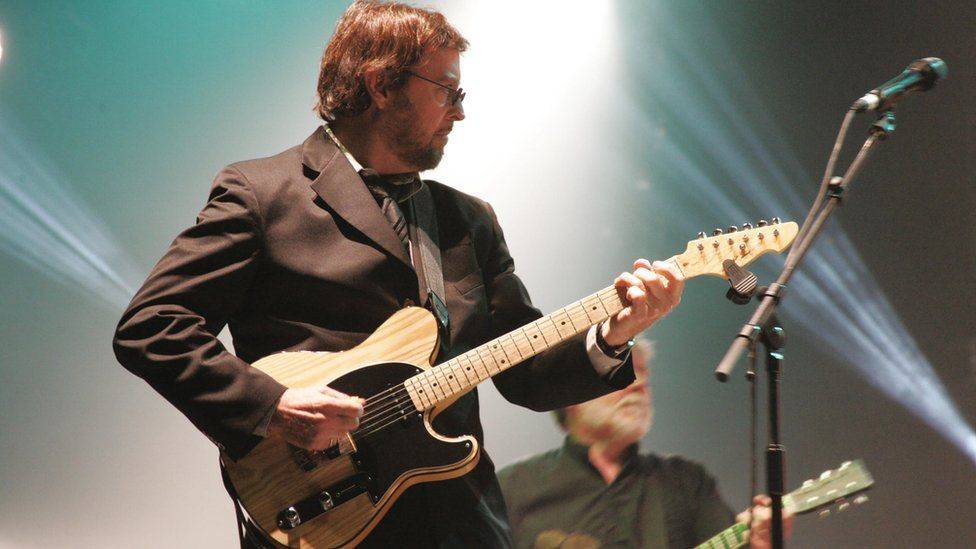

In 1950 Fender debuted their first solid-body electric guitar. Designing it seemed to be easier than naming it though. The guitar went through a number of branding changes. For a very short time, it was known as the Broadcaster. It was soon changed however to avoid confusion with the Broadcaster drum kits made by Gretsch. For an even shorter time, it was transitionally known as the ‘No-caster’, only because it didn’t actually have a name on the headstock, until Fender finally settled on the now iconic name, Telecaster.

The Telecaster was simple. So simple in fact that it was first derided by most musicians who saw it. No carved arched tops or intricate marquetry. Just a solid plank or originally Pine, bought from the local sawmill, cut into a ‘rough’ shape. It didn’t take long for guitarists to fall for the sound that was possible from this stripped-back guitar. The distinctive ‘twang’ of a Telecaster was something totally new and is still sought after today.

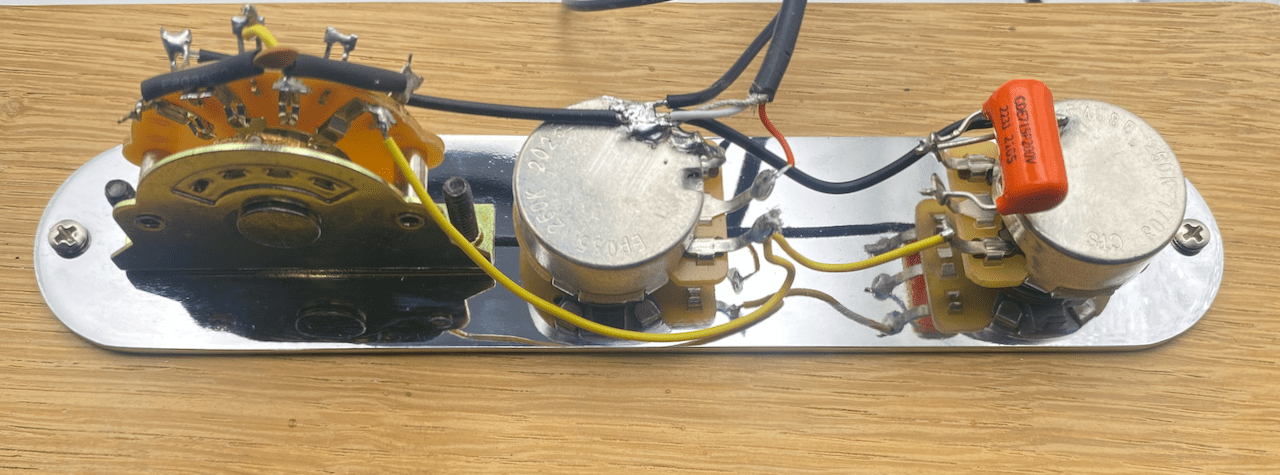

Fullerton was able to use his past experiences to help Fender streamline their mass production of their instruments. From the design phase onwards, the manufacture had to be simple and repeatable many times over with a high degree of accuracy. Specialised tools and processes were produced to maintain a high level of quality throughout the build process.

Bringing in concepts like the bolt-on neck and the method of incorporating the truss rod into a channel, mounted from the rear of the neck and covered with what is still referred to as a ‘skunk strip’ also completely changed how electric guitars were built. These ‘radical’ design changes are still used by multiple companies throughout the world.

Designs and Patents

During his tenure with Fender, the list of designs that George Fullerton worked on as part of the research and development team is jaw-dropping. These are just some of the highlights:

1950 – The Telecaster. The original, and some may argue, still the best. The benchmark of solid body design, with a bolt-on neck and easy assembly, made the Telecaster the guitar that changed the industry.

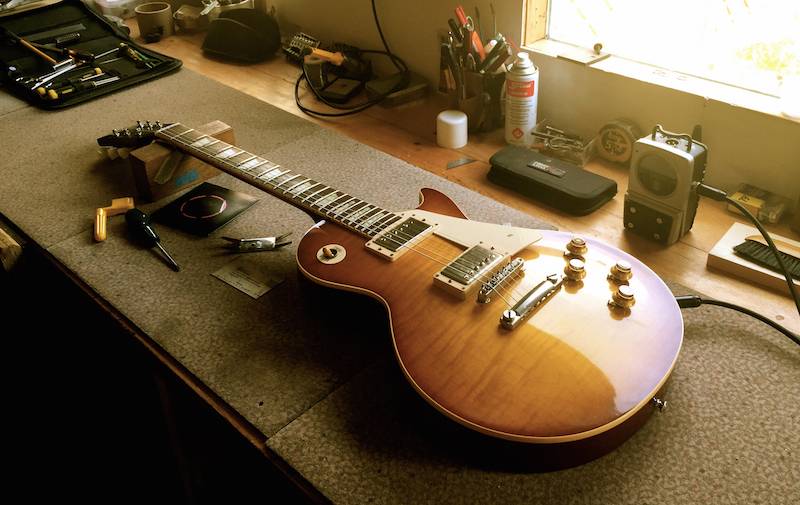

1951- The Precision Bass. During the design phase of the Precision Bass, the issue of scale length was hotly debated. George recalled in an interview that “.. we tried some sorted scale lengths, like 30” or 32”, but they seem to get the resonance we needed. We even tried 36”, but the distance was too long and the distance between frets became impractical to play. Eventually, we settled on a 34” scale.” This is still an industry standard today.

1954 – The Stratocaster. When this guitar first launched, that was exactly what people thought – that it had launched from another planet and landed on Earth to change things forever. The heavily contoured body design looked like nothing people had ever seen before. That fact that Fender could achieve this while also mass-producing this instrument in multiple colours literally did push Fender to the Moon.

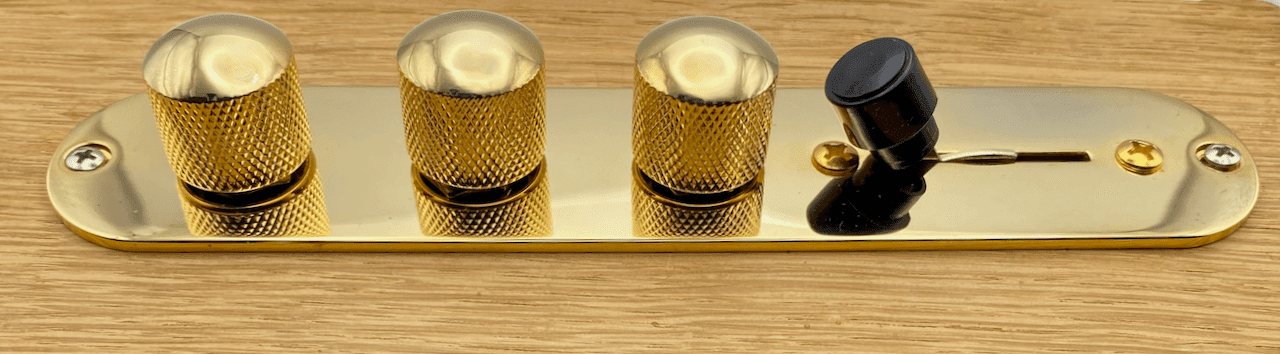

The Tear-drop jack plate – an iconic part of the Stratocaster’s radical design. The revolution didn’t stop at the body shape. George designed the innovative jack plate shape to prevent damage to the instrument if the instrument cord was accidentally pulled out of the body. It protected the plug itself, incasing in within the front of the body rather than sticking out of the edge of the lower body. Its tear-drop design added to the flowing lines of the rest of the body.

George’s wife, Lucille, also helped with the marketing when it came to the Stratocaster. It was Lucille who suggested the phrase “Original Contour Design” which still appears as a decal on the headstock of the Stratocaster to this day.

Taking inspiration from the automotive industry, the ’Custom-color’ concept, allowing customers to choose the finish of their guitar bodies was introduced in the late ‘50s.

Fullerton was working as Vice-President of Production in 1965 when Leo Fender retired and the company was sold to CBS. He stayed in his role with the company until 1970.

Beyond Fender

After retiring from Fender, George briefly worked with Marie Ball to develop the Earthwood guitars and basses. He then joined Leo in the mid-’70s to form the original Music Man company.

The pair went on to found, with ex-Fender salesman Dale Hyatt, another guitar company, G&L.

Regarding G&L, Fullerton is quoted as saying “…What Leo tried to do with Music Man guitars, and later, G&L, was design guitars through his CLF Research company that didn’t look like the instruments he’d designed at Fender, He wanted these newer brands to be improvements on his earlier designs. In a lot of ways, he had his work cut out for him. But he felt his later designs were the best he’d ever done.”

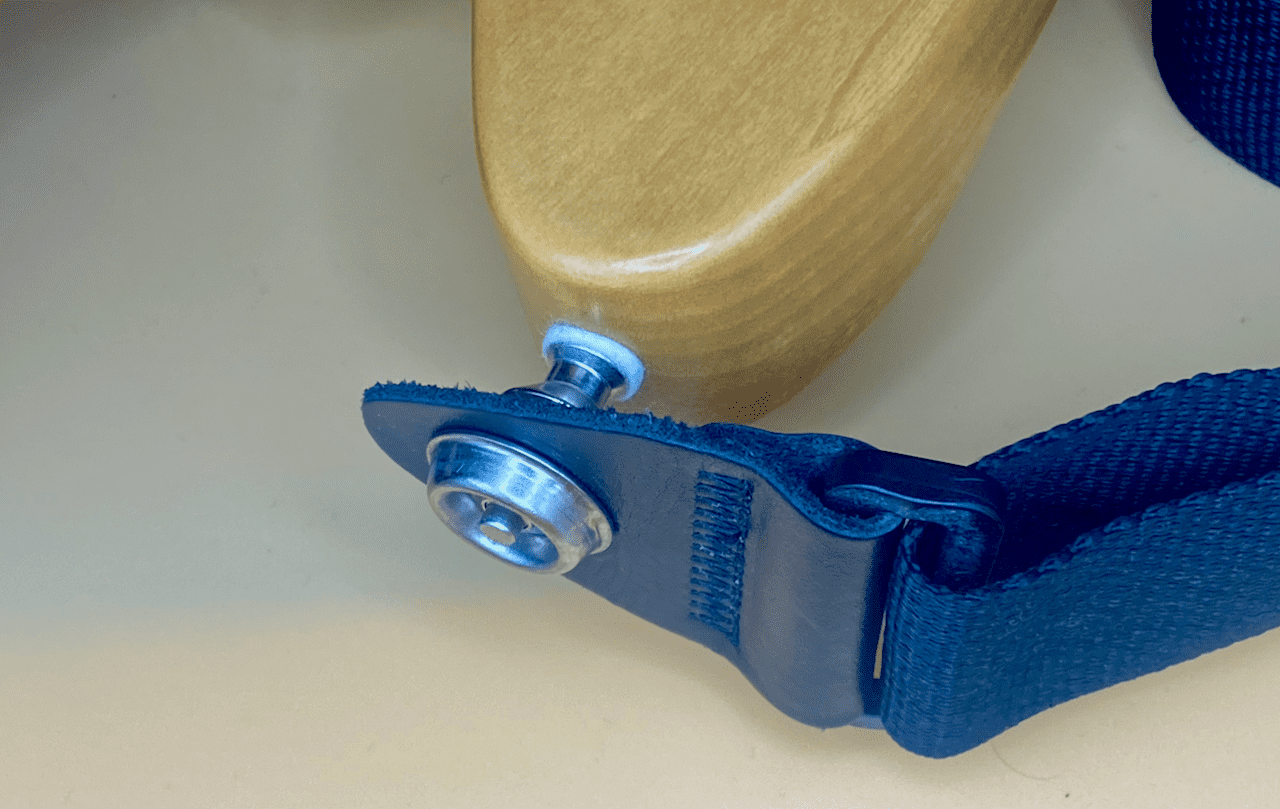

Fullerton continued designing and had even more patents while working for G&L. One of which was the three-bolt tilt-neck adjustment. A design he had first used while with Fender. But this improved design took things a step further.

“The problem with the Fender type was that as the neck was adjusted, there was a shaft inside that was turning against a metal plate on the bottom of the neck, changing the angle,” he recalled. “This meant not enough vibration from the strings was being conducted through the neck joint because contact between the neck and the body was lessened; there was a gap. My neck patent assured that a neck could be tilted while maintaining contact between the neck and the body.”

In the mid-’80s, George underwent bypass surgery. On the advice of his doctor, he sold his stock in G&L to Leo and reduced his work to more of a consultant position.

When Leo passed in March 1991, George helped design his headstone.

In ’07, Fullerton became a consultant at Fender Custom Shop. In November of that year, Fender produced the 50th anniversary George Fullerton Stratocaster.

Lucille Fullerton died on the 20th April 2009. George Fullerton passed 11 weeks later.

Fender and G&L both paid tribute to George on their websites. List all his accolades and achievement with both companies.

Bill Carson’s widow, Susan recalled ‘ …He [George] was truly Leo’s right-hand man, and he seemed to admire Leo very much; his loyalties to Leo were unmatched. George has been an under-recognized and under-appreciated figure in the guitar industry, and I would hope his memory would be elevated to that which he deserved.”

The final question for Fullerton in the ’91 interview was whether the label “unsung hero” was appropriate in his case. Fullerton’s response? “Well… maybe.”